21.11.2017 | André Clerc

Priceless: New Swift Rules for Financial Service Providers

Last year, hackers almost managed to pull off one of the biggest fraud cases of all time and steal almost a billion US dollars. The SWIFT network is now exerting pressure to strengthen IT security in the banking network across the board.

It was an operation that had all the makings of a thriller. In February 2016, hackers who are still unknown managed to exploit the SWIFT payment network for their criminal purposes. They misused access rights and systems at Bangladesh Bank to feed 35 payment orders with a total value of over 950 million US dollars from the bank’s account at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (New York FED) directly into the SWIFT network. The hackers almost pulled off an incredible coup had it not been for further manual controls that prevented the greatest damage.

Nevertheless, the hackers managed to process five of the 35 payment orders. The damage was still considerable, as around 81 million US dollars ended up in four private bank accounts of the hackers in the Philippines (further information can be found at www.ix.de/ix1712104). It was subsequently no longer possible to trace these payments or the further course of the transaction.

Difficult search for the vulnerability

The search for potential vulnerabilities proved to be extremely difficult. It quickly became apparent that the SWIFT-side components (software, hardware, protection systems, SWIFT network, etc.) were not affected. Instead, insufficiently protected environments, end systems and accounts on the customer side were exploited. In addition, software components, such as a PDF reader, were modified in such a way that manipulated payments could no longer be recognized. If hackers manage to gain access to a SWIFT user’s administrator rights, SWIF’s bulwark can only limit any potential damage. Based on the findings of the vulnerability search, SWIFT published a statement in May 2016 stating that every SWIFT user - i.e. holders of a Business Identifier Code (BIC 8) - must continue to take care of their own internal security. In addition, a self-declaration on the status of internal IT security must be submitted in future.

The news agency Reuters subsequently reported that the intrusion into the systems of the damaged bank was primarily due to an inadequate security infrastructure (see “All links”). Unsuitable and inadequate hardware had been used, and effective protection systems such as firewalls and vulnerability scanners had been omitted at key points - fatal errors that ultimately made it easy for hackers to infiltrate the company.

It became apparent that the IT security concept of the bank in question had considerable shortcomings. In addition, the attackers were not only fully aware of the software and IT infrastructure in use, but also knew exactly where the weak points were and when to launch their attack.

Representatives from Bangladesh Bank, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and SWIFT met to find out what the security gaps were that made the fraud possible. Their aim was not only to track down the criminals but also to find out all the details of the case so that the global financial system can be better protected against such attacks in the future.

Fears that further attacks on a similar scale could follow were confirmed: over the course of the year, SWIFT reported attacks with malware, all of which again affected bank-side components.

The hackers’ approach was the same each time and hardly differed from other attacks. First, they gained access to a financial institution’s customer-facing systems. In the second step, they gained access to the user data of employees who can create, confirm or send SWIFT messages. They then used the stolen user data to smuggle in fake messages and remove or falsify possible traces and evidence.

To falsify evidence, the perpetrators manipulated a PDF reader that the affected employees of the financial institution used to read SWIFT messages. This had already been installed as malware on the work computers beforehand and hardly looked any different from the original. However, when the reader was used to read the payment confirmations, the corresponding documents were distorted or even deleted altogether.

In all known cases of fraud, the cyber criminals exclusively exploited vulnerabilities in the IT systems used by customers to send manipulated SWIFT messages via the SWIFT network. The corresponding controls and protection mechanisms of the financial institutions were bypassed. But what was even more serious: by deleting or falsifying the statements and confirmations, the victims were only able to recognize the fraud after a delay.

Such a perfidiously planned attack could theoretically have affected anyone, as the attackers are highly professional criminal organizations. They sound out every conceivable weak point and start where they find the worst protection.

IT systems put to the test

In order to prevent the infiltration of fraudulent payment orders in future, the SWIFT Association saw no other way than to impose certain requirements on all SWIFT users (financial institutions, pension funds, industrial groups, etc.) regarding the use of its infrastructure. The security of the customer-side environments and in particular the channels for data transfers and payment transactions should be the focus. Because one thing was certain: the perpetrators must have hacked very deeply into the IT systems of the organizations concerned over a long period of time before their big coup.

The guidelines for using the SWIFT infrastructure require all participants to provide detailed information on how they protect themselves against cyber attacks. Conversely, the users themselves asked SWIFT for assistance in this area. However, in SWIFT’s opinion, the requirements alone are not enough to prevent potential damage. For this reason, users are also expressly requested to exchange information promptly in the event of suspected fraud.

The SWIFT network has launched its Customer Security Program (SWIFT CSP) under the headings “Secure and Protect”, “Prevent and Detect” and “Share and Prepare”. An initial draft was sent to all users for review at the end of October 2016. It was primarily designed for smaller SWIFT users with a rudimentary IT security infrastructure.

For security and protection, the SWIFT CSP now also includes the aspects of prevention and detection as well as information exchange and preparation in the event of possible fraud. Previously, customers were only required to protect their own environment (Fig. 1).

Stumbling blocks for large organizations

Large organizations felt that the measures contained in the draft were not practicable enough and there was therefore strong resistance from their side: their existing, professional security systems would have been virtually undermined by these new measures and controlled, automated processes would have had to be at least partially replaced by manual procedures.

This was followed by a statement from the SWIFT network, in which the Swiss participants also had their say with regard to these negative consequences. As a result, the guidelines were revised. Although the detailed recommendations remained valid, they were supplemented by more generous leeway for alternative implementations.

The security requirements now in force, which are set out in the SWIFT Customer Security Controls Framework, require customer-side protection of components that are directly connected to the SWIFT network. The effective protection and restriction of credentials used to access SWIFT systems and the response to possible attacks are also mandatory.

The SWIFT requirements correspond in principle to the measures already implemented or at least planned for implementation in larger organizations with a high level of security awareness. Nevertheless, it can be assumed that a large proportion of SWIFT users will have to implement necessary improvements to their security concept.

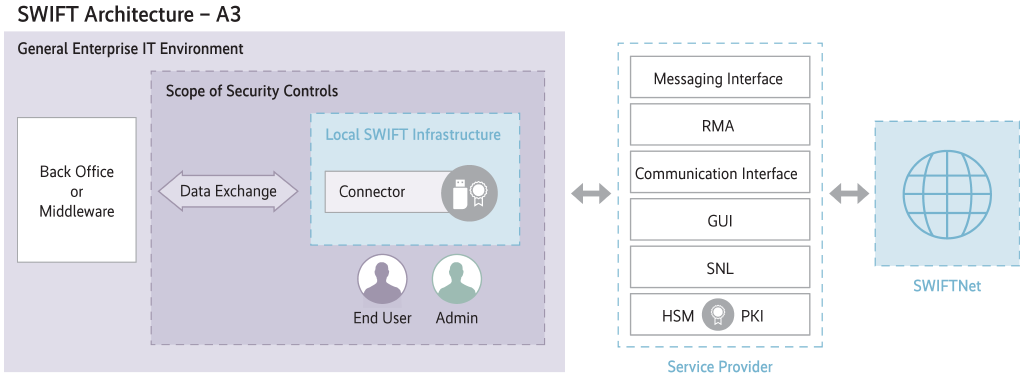

With the required scope of application, SWIFT goes much further than the financial market supervisory authorities in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, for example. The requirements are not only aimed at banks and financial institutions, but at all holders of an eight-digit BIC. This means that in future the requirements will also apply worldwide to insurers, pension funds and industrial groups. Even if a BIC holder obtains SWIFT services via a service bureau, it is still obliged to implement the requirements and must submit a self-declaration of the 16 or 11 mandatory security controls, depending on the infrastructure type (Figure 2).

As SWIFT is not a regulator, the new requirements only apply to SWIFT components. However, it is strongly recommended that the required measures be implemented throughout the group and that all IT components be included. In this way, the security of a company as a whole can be increased. A central element is strong authentication of employees to the IT systems, which ultimately leads to effective protection against the theft of credentials.

With a company-wide implementation of the security measures required for SWIFT components, many of the spectacular and media-effective hacker attacks of recent months could have been prevented or at least limited in their impact. These include the WannaCry and NotPetya attacks, which caused devastating damage to companies, hospitals and public authorities worldwide.

In other cases, such as the Heartbleed bug, which made prominent websites, VoIP phones, routers and network printers vulnerable to attacks, efficient incident and change management would have made it possible to patch the affected systems more quickly.

The specified measures depend, among other things, on the type of infrastructure. In addition to three other architecture types, this type uses a software application (in the example Alliance Lite2 AutoClient for file exchange) within the customer environment to provide communication between applications with an interface to a service bar (Fig. 2).

Based on other standards

SWIFT has not reinvented the wheel with the currently defined measures and controls. Rather, the security controls are closely based on international standards such as the Cybersecurity Framework of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), ISO / IEC 27002 or the security standard of the credit card industry PCI DS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard) (see “All links”). They can even be transferred to these standards (so-called mapping) in order to apply existing security infrastructures to SWIFT components.

Although SWIFT users only have to comply with 11 or 16 of the 27 security objectives - the others are only “recommended” - it is advisable to implement the measures in full to ensure effective protection against attacks.

Among other things, the following points should take center stage:

- Protection of the local (SWIFT) environment;

- Control of privileged accounts on the operating system;

- Security of internal data streams;

- Installing security updates regularly;

- System hardening: analysis of systems and subsequent hardening to reduce vulnerabilities;

- strong (multi-factor) authentication and logical access control;

- Optimize protection against malware;

- Check software integrity;

- Logging and monitoring of activities;

- Planning defense mechanisms in the event of cyberattacks.

The last point in particular should not be neglected: Anyone who has not drawn up a plan to defend against attacks is taking a high risk - there is a risk of financial losses and reputational damage. Although most larger organizations have such a plan, many small and medium-sized companies still lack one. No wonder that even the US Homeland Security is addressing the issue and calling on American companies to take action (“All links”).

SWIFT puts pressure on

Time is slowly running out for SWIFT users, as all holders of a so-called BIC 8 must submit a self-declaration by the end of December 2017, indicating the degree to which the prescribed security check has been fulfilled. However, submitting it once is not enough: The self-declaration must be renewed at least every twelve months, and the same applies in the event of a change to the local IT system environment.

In January 2018, SWIFT will also introduce a monitoring system and increase the pressure on participants to cooperate. From then on, the regulators - such as the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) for Switzerland, the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) in Germany and the Financial Market Authority (FMA) in Austria - can be informed which organizations have not yet submitted the self-declaration. Finally, full compliance with the SWIFT requirements must be achieved by December 2018. Here too, SWIFT intends to monitor compliance and report to the regulators those institutions that do not comply with the rules.

For those who require external support in analyzing and implementing the SWIFT requirements, SWIFT has compiled a list of registered cybersecurity providers (“All links”).

With the implementation of the SWIFT requirements and the recommendations from NIST, BSI or ISO / IEC, it will be much more difficult for cyber criminals to achieve their goals. However, it will be necessary to regularly review the current measures and requirements - especially in view of the highly professional, well-organized and highly motivated attackers who are tirelessly searching for new targets. And despite all their efforts, criminal organizations will continue to succeed in identifying and exploiting the weakest link in the chain.

All links: https://www.heise.de/select/ix/2017/12/softlinks/104

Note: This article was published in the journal iX 12/2017.

Compliance Information Security Management System (ISMS)